What Louisiana State Penitentiary Offenders Taught My Students and I about Great Teachers

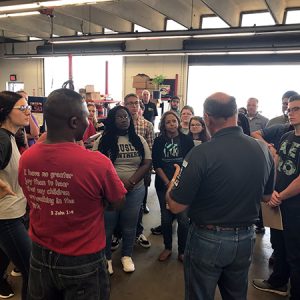

For the past two years, I’ve taught a course called Educators Rising, aimed at exposing high school students to the teaching profession that our students desperately need us all to see: a means to social justice, a grantor of access, a hero training of sorts where we each figure out how best to change the world. This year, however, I knew that if I was going to teach my students about the systemic impact of poverty, and race, and disabilities on a person’s educational experience, I would need to provide experiences that transcended numbers, figures, and books. I wanted to take them to the last stop of the K to Prison Pipeline so that we could retrace our steps. My students realized that in the data we viewed and the research we read, there were some voices and stories missing: those belonging to the inmates. They wanted the chance to understand a human experience from a perspective we seldom get to hear first-hand. What better place to go than to a prison where over 80% of the offenders never finished high school or any other formal education?

As we went through gate after gate, we finally got to the school building where we noticed posters hanging warning about the dangers of Extortion and reminders that Sexual Assault is an Act of Violence. These were already in stark contrast to Brusly High School’s Taylor Swift Drink Milk posters warning of the dangers of calcium deficiency.

But what happened once we entered the classrooms themselves, the entire atmosphere shifted and it no longer felt like a prison. It felt like a future. Just like any classroom, the walls of their HiSET (former GED) classes were filled with posters of periodic tables, food pyramids, geometric shapes, algebra formulas, planets and even a revision checklist! I teared up when I looked at the bulletin board and saw a motivational message: Shoot for the Stars.

I couldn’t help but think back to something that Gary Young, the assistant warden, had impressed on my class before we even got off the bus. He said that the penitentiary “had to start taking a more holistic approach. He said it’s not just about educating the mind. It’s about educating the heart. You gotta go for the heart, otherwise if they attend our school here, we’ll just end up with smarter criminals”

Now… this idea of educating or nourishing the heart is at the heart of social and emotional learning in schools, but to hear it as the cornerstone of learning at a prison made for people serving life sentences gave us all a shock. Perhaps it was because this approach to teaching has not traditionally been supported in our schools. But we saw it in the classroom and we were in immediately. As my students engaged the offenders in round table conversations, we could immediately see the pride they had for their new shot at an education. One man had been trying to get his GED for 20 years and is now within arms reach of his HiSET diploma in January 2020 if he just passes reading. 20 years! That’s grit! He accepted the consequences of choices that placed him in the prison system, but said that teachers here made him feel he could finally achieve something, even if it took a while.

We also heard some sadder stories, marking experiences in our education system that were devoid of culturally responsive teaching, dignity, and social and emotional care. One offender hated school since fifth grade when a teacher in the late 70’s told the class that as an African-American, he was still part ape and hadn’t fully evolved. Another man said his fourth grade teacher made a prediction to the class that half would end up pregnant, dead, or in prison by the end of high school. She didn’t have very high hopes for the other half, either.

But the thing is, despite some of these key examples of how schools failed to keep their promise for a good education by failing to support the social and emotional learning of these men as children, two things were clear: 1) They, in no way, blamed past teachers for the terrible choices they’d made and 2) Their current opinion of school was very different today and they attributed the shift solely to their teachers at the penitentiary.

However, what’s fascinating about the teachers and mentors at Louisiana State Penitentiary is that they’re nearly ALL offenders! In fact, there are only three full-time, certified teachers. But every single teacher is trained on holistic learning that puts the learner at the center and ensures the emotional needs are met. The expression of these outcomes became the best professional development for teaching that I’ve ever had and the most powerful experience I could’ve hoped for my rising educators.

Every offender remarked that what was different about school this time around was discovering that

- Education should be used to better help those around you,

- Each teacher took the time to learn each student to find out where their potential was and

- Each teacher worked with them to see the possibilities in a world behind bars that were nearly invisible to them when they lived on the other side of them.

As my students broke off into small groups to lead discussions, I heard them ask the offenders for advice they would give to anyone considering becoming a teacher. These men have life sentences in prison and are striving for GEDs but the advice was exactly what every teacher needs to hear:

- Be mindful of words you use and choose around the students. They’re listening, watching and “they’re not dumb”.

- A teacher can change the direction of a life. They can make a child gain or lose a dream.

- Challenge EVERY student. Not just the ones you think have the best shot.

- Learn your students as quickly as you can. They desperately need you to.

Truly, these offenders were helped to understand that their job is to help society and communities, even from inside a prison. They not only benefited from incredibly high expectations but felt empowered and loved. They were being taught social and emotional skills and how self-management and resilience can make all the difference in the world.

Considering that these ideas are the very foundations of social and emotional learning, no one at Louisiana State Penitentiary calls it that. They just know that these elements have to build the foundation of their reentry program if they’re to ensure their safety. By also ensuring dignity and quality of life, offenders, even after realizing they may never see beyond the barbed wire, know that they are still worthy human beings capable of making their world a better place. Back on the bus as we reflected on the experience, there were few dry eyes when one of my students remarked, “It’s a shame that some of them had to go to prison to get their first great teacher. We need to do better.”

That’s really the heart of the matter. Long before I knew the jargon or buzzwords for social and emotional learning, I knew that my classroom had to be a safe place for students to explore, feel valued, and discover their potential. Much like the approach of the assistant warden, I realized that if I didn’t ensure that education in my class involved relationship building through human connection, I was just going to churn out really smart robots who didn’t care enough about any problem to bother to solve it.

Part of the power of teaching is that once we find out something exists, we find a way to harness its power so that we can give it to our kids. In this case, my Educators Rising students and I discovered that great teaching through attention to and empowerment of human beings goes a long way in delivering a true education, capable of changing the world around us. Content alone simply can’t hold a candle.

This experience certainly changed more than a few viewpoints of my students who were still resisting the call to be educators. After that day, they felt a sense of hope and purpose in education. Through an authentic experience, the teachers and offenders at Louisiana State Penitentiary showed my students a different view of what it means to teach. They showed us all that if we present education as a means to change, then we are giving each of our students a life-long key to unlock the barriers around us… whether made out of steel bars, fear, or disbelief that any one of us has the ability to make the world better.

Kimberly Eckert teaches Educators Rising and serves as the Innovative Programs Coordinator for West Baton Rouge Parish Schools in Louisiana. She holds a BA in social work, an MEd in Special Education, and is currently pursuing a PhD in Learning, Innovation, and Instruction. Eckert has been teaching for 11 years, is a national fellow for Understood.org, an expert teacher for NCLD (National Center for Learning Disabilities), a 2019 NEA Social Justice Activist of the Year national finalist, 2018 Louisiana Teacher of the Year, and the 2018 Louisiana Public Interest Fellow.

Class Website: https://sites.google.com/wbrschools.net/eckertsecksperts/home

Twitter: @2018LaToy

Facebook: @2018LaToy

Instagram: @2018LaToy