Guest Writer: Amanda Brunson

AMANDA BRUNSON

Director of Women’s Policy

Office of the Governor

Women’s History Month

March is National Women’s History month, a time for us to celebrate the contributions that women have made to the advancement and well-being of our country. In Louisiana, you don’t have to look far to find incredible women who’ve worked tirelessly to improve our lives. Rather than a rising tide lifting all ships, let’s think of these women and each of us as links on a chain. As we thread our arms together and connect our work, from the small acts to the big acts, from the past to the future, we are building an unbreakable force that is hoisting our country a little bit closer to the safe, equal and prosperous future that we all desire.

Louisa Williams Robinson, a Coushatta woman born in 1855, served as a tradition bearer, passing along her community’s values, stories and language to her children and grandchildren. Coushatta women, through their role in trade, helped increase understanding and protection of the preservation of their culture. With the skills learned in making and trading items, and despite not knowing how to read or write English, Robinson successfully navigated legal systems to fight for the rights to her father’s property and the transfer of her property to her children. Her daughter, Sissy, became one of the first native women to receive land under the Indian Homestead Act. She was single and only 18, navigating the legal system through her mother’s influence and focus on education. This was the only land brought into trust by the federal government, which helped to reestablish the Coushatta’s status as a federally-recognized tribe. Continuing the generational pattern of legal prowess, Sissy’s daughter, Annie, successfully fought for custody of her younger siblings upon the death of her parents, a role typically conveyed to men.

Many of us can instantly recognize the work of Clementine Hunter. Born in 1887, Clementine worked first in the cotton fields and later as a domestic servant at Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches. When cleaning the room after a visiting artist left the plantation, Hunter discovered a handful of paints. She told Francois Mignon, the organizer of culture at the plantation, that she thought she could make a painting if she “sot her mind to it.” When she showed him her painting the next day, Mignon told her he could make her famous. Hunter is known for painting on a variety of surfaces, including boards and bottles. Her works depict life on a plantation, from the hard work to the mundane tasks to life’s celebrations and milestones. Interestingly, she painted more than 100 abstracts at the request of a writer who supported her work through the years, but she stated that they were harder than the works she painted from her memories. She was the fourth person and the first African American to be given an honorary doctorate from Northwestern State University of Louisiana.

The first commercial Cajun music recording was the work of Cleoma Breaux Falcon and her husband Joe. Born in Crowley in 1906, Falcon became a primary caretaker of her rowdy brothers when her father abandoned the family and her mother went to work. She played music with her brothers in local dancehalls to help contribute to the family’s income. Cleoma pushed boundaries by playing music outside of the home, which was against the custom of Cajun families. In the mid-1920s, she and her brothers began playing with another musician, Joe Falcon. Joe and Cleoma, who eventually married, caught the attention of a Columbia executive who was scouting for talent in New Orleans. Their first record was a hit and led to record companies recording other Cajun musicians.

We are lucky to also count Rowena Spencer among our predecessors. Spencer was born in 1922 in Shreveport, though her family eventually moved to New Orleans and then Catahoula through her early years. The eleventh doctor in her family, Spencer had many role models but was nevertheless subjected to gender discrimination under the post-World War II notion that women belonged at home. Spencer completed her undergraduate studies at Louisiana State University and became the first female surgical intern at Johns Hopkins. She returned to LSU to become the first woman to study pediatrics and general surgery. She went on to specialize in conjoined twins after completing the first separation of newborns in 1954. Spencer was the first female surgeon in Louisiana, the first pediatric surgeon in the state and the first female to join the LSU Medical School surgical staff in a full-time position. These are even more remarkable feats when you learn that she wasn’t allowed in the doctor’s lounge and had to stand behind a curtain and only listen when she and her fellow male residents were receiving instruction in how to examine adult males with hernias.

Alas, where would we be without Oretha Castle Haley? Though born in Tennessee in 1939, Haley called the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans home from the age of seven. She began her work in the grassroots civil rights movement as a student at Southern University New Orleans. Eventually working her way up to president of the New Orleans chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, Haley built upon her family’s strong support of the civil rights movement and led sit-ins and demonstrations across the city. In one operation, Haley and her fellow demonstrators were assaulted by so many chemicals that the fumes forced the owner to close early. Her arrest, with others, related to a sit-in on Canal Street eventually led to the historic Lombard vs. Louisiana case, which was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1963, leading the New Orleans CORE chapter to become one of the most famous in the country. Her successful leadership led to her promotion to field director for all of north Louisiana, a position that was only held by one other female in the nation. When she returned to New Orleans, Haley became an advocate for anti-poverty initiatives and led the campaign that saw Dorothy Mae Taylor become the first African American woman in Louisiana’s legislature.

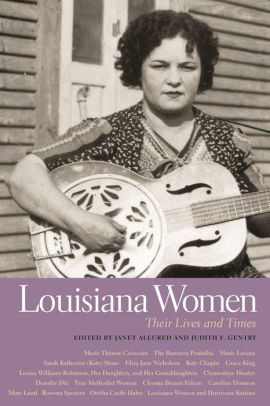

From Natchitoches to Crowley, from Ouachita to Allen Parish, from art and music to legal advocacy and civil rights, so many powerful women have carved the spaces and places we fill today. The book Louisiana Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Janet Allured and Judith F. Gentry, contains these stories and so many more.

In 1909, the first National Women’s Day was held to honor the women who protested in 1908 against their working conditions as garment workers. Next year, in 2020, we’ll celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment. It is so hard to comprehend that we’ve only had the right to vote for 100 years. That’s within the lifetime of most of our grandmothers. May we all express that right as we vote on elected offices each and every year. Despite our great strides and despite the fact that we comprise 51% of our state’s population, only 15% of our legislators are women. You know that saying, “nothing about us without us?” There are many Louisiana women running for legislative seats this year. There are also plenty of other ways women are seeking to lead: on local boards and councils, as grassroots advocates and on statewide boards and commissions, to name a few.

The Louisiana Women’s Policy and Research Commission identified several priority areas this year: Equal pay for equal work, raising the minimum wage, paid family leave, freedom from violence and sexual harassment, improving maternal health and birth outcomes, encouraging women to enter STEM fields, improving access to affordable and quality childcare, and improving access to reproductive, contraceptive, substance use and mental health services. In every one of these areas strong women have brought us to where we are today, and strong women will continue to form new links to that collaborative chain.

So, women’s history isn’t just about the past: we continue to create it. Whether you choose to make your mark through a career or volunteerism or through giving your children (or someone else’s children) a safe, stable nurturing environment, you are a link in our chain. May we always remember that we aren’t in it alone, that there are strong women on either side of our history.